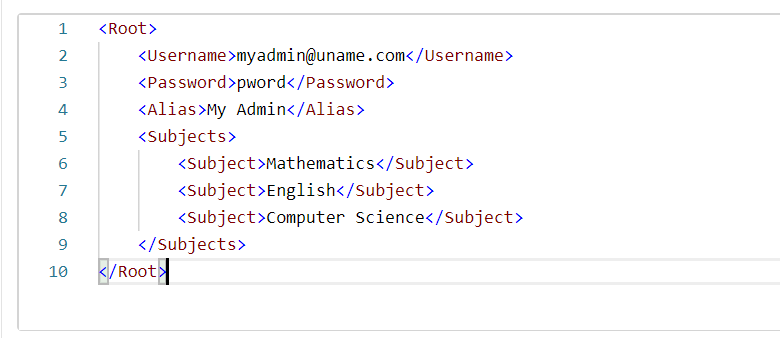

import_all_aljz.xml

Why Qatar is betting on diplomacy with Iran

The confrontation between the United States and Iran has entered a more volatile phase, marked by direct military strikes, heightened rhetoric and the steady erosion of long-standing restraints. From attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities to Tehran’s calibrated retaliation across the region, the risk of escalation has become tangible rather than theoretical. For Gulf states, whose security and economic stability are directly exposed to any US–Iran conflict, the implications are immediate. It is within this environment that Qatar’s diplomacy between Washington and Tehran should be understood: not as neutrality for its own sake, but as a calculated effort to contain risks that escalation would only magnify.

Periods of heightened tension between the United States and Iran have long carried consequences well beyond Washington and Tehran. Following a wave of protests inside Iran that, according to varying estimates, resulted in the deaths of several thousand people, rhetoric between Tehran and Washington has hardened markedly. This included President Trump’s threat to intervene on behalf of the protesters, a development that further heightened the urgency of diplomacy in the Gulf. The Gulf’s geography, concentrated energy infrastructure and interlinked security environment mean that even limited confrontation risks rapid regional spillover. Against this backdrop, Qatar’s approach toward Washington and Tehran has consistently prioritised de-escalation, mediation and the maintenance of political channels at moments when such channels appeared increasingly fragile.

Qatar has emerged as an effective and credible mediator at moments of acute tension between the United States and Iran, offering practical avenues that have helped prevent crises from escalating further. Drawing on its sustained relations with Tehran and its strategic partnership with Washington, Doha has maintained discreet and trusted channels that allow both sides to communicate when direct engagement becomes politically constrained. This positioning has enabled Qatar to facilitate de-escalatory outcomes that have saved face for both parties, reinforcing its role as a mediator that creates political space for restraint rather than confrontation.

This role was most visibly demonstrated in September 2023, when Qatar helped facilitate a prisoner exchange between Iran and the United States, alongside the release of frozen Iranian funds for humanitarian purposes. The process required months of indirect negotiations, careful sequencing and political reassurance on both sides. While the agreement did not signal a broader rapprochement, it underscored an important point: even amid deep hostility, diplomacy remains possible when credible mediators are available.

For Doha, such mediation is not an end in itself. It reflects a broader conviction that the Iranian nuclear issue, and US–Iran tensions more generally, cannot be sustainably managed through coercion alone. Qatar has consistently aligned itself with the view that dialogue rather than military action offers the only viable path toward containing risks and preventing escalation. This position does not imply indifference to Iranian regional behaviour or to proliferation concerns; rather, it reflects an assessment of costs, uncertainty and unintended consequences for regional security. As such, even in the aftermath of Iran’s calibrated missile strike on the Al Udeid airbase in Qatar — a Qatari military facility hosting US forces — launched in June 2025 in response to US attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities, Doha moved swiftly to engage both sides and contain the crisis. Through urgent outreach and established communication channels, Qatar contributed to broader efforts that helped support a fragile ceasefire that has broadly held since, underscoring both its capacity to be effective in mediation and the trust placed in Qatari diplomacy.

A military confrontation aimed at overthrowing the Iranian regime would almost certainly generate effects that extend far beyond Iran’s borders. Internally, such a scenario risks producing state collapse, fragmentation of authority and the re-politicisation of ethnic and sectarian identities within a large and highly complex society. Externally, the spillover effects could include large-scale refugee movements toward neighbouring states, including across the Gulf, as well as severe disruptions to maritime security and energy markets. Taken together, these outcomes would pose immediate challenges to Gulf states whose own stability is closely tied to regional calm.

Recent developments in the region have already altered the strategic balance. Since the October 7 attacks and the subsequent regional confrontations, Iran’s network of allied non-state actors has come under sustained pressure. Several elements of the “axis of resistance” have been weakened militarily and politically, reducing Tehran’s ability to project influence in certain theatres. At the same time, the US attacks on Iran in June 2025 have dispelled any remaining misconception about Washington’s willingness to strike Iran directly and degrade its nuclear enrichment capacity.

From a Gulf perspective, however, further escalation offers diminishing returns. Weakening Iranian regional influence does not automatically translate into regional stability, particularly if pursued through strategies that risk state collapse. For Gulf states, the priority is not the dramatic remaking of Iran’s political system, but the avoidance of chaos that would be costly, unpredictable and difficult to contain. This assessment is not limited to Doha. In recent years, Qatar’s position has increasingly converged with those of Saudi Arabia and Oman, both of which have invested in reducing tensions with Tehran through dialogue and confidence-building measures. Their efforts to communicate the risks of military escalation to the Trump administration reflected a broader regional mood, one that favours containment and engagement over confrontation. This convergence is notable given the political differences that have historically separated Gulf capitals.

Qatar’s mediation efforts offer a pathway that helps prevent regional chaos at a moment when escalation increasingly offers diminishing returns. By keeping channels open, facilitating limited agreements and discouraging maximalist strategies, Doha seeks to reduce the likelihood of miscalculation. Such efforts rarely produce dramatic breakthroughs, and they are often invisible by design. Yet their absence would likely make escalation more probable, not less.

In an increasingly polarised regional environment, the value of de-escalation is easily overlooked. It lacks the clarity of deterrence and the euphoria of military action. Still, as Qatar’s engagement between Washington and Tehran illustrates, diplomacy, however incremental and imperfect, remains one of the few tools capable of preventing crises from spiralling into wider conflict. In a region where the costs of war are shared far beyond the battlefield, that contribution should not be dismissed lightly.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Does the World Economic Forum still matter in a fractured global economy?

The annual pilgrimage of the world’s political and corporate elite to the World Economic Forum in Davos has come at a critical point.

Geopolitical tensions are at fever pitch.

The US is led by a president openly sceptical of multi-lateral cooperation and open trade.

Donald Trump is using tariffs as a tool for economic and political leverage, threatening to dismantle the global order.

Critics say the summit is long on talk and short on action.

But supporters say keeping rivals talking may help contain some of the world’s biggest problems.

And who pays to rebuild Gaza?

Plus, Iran’s economic crisis.

‘Imperial’ agenda: What’s Trump’s Gaza development plan, unveiled in Davos?

Glittering towers lining the Mediterranean coastline, a “New Gaza” and “New Rafah” in the offing, with more than 100,000 housing units alongside orderly industrial parks – and even a new airport.

All without consultation with the people this development is supposed to benefit.

This is the skeleton of a “masterplan” for post-war Gaza, presented by Jared Kushner, United States President Donald Trump’s son-in-law and a real estate developer, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland this week.

“There is no Plan B,” said Kushner, as he unveiled the ambitious plan.

Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza has killed more than 71,000 Palestinians – with thousands more missing and presumed dead under the rubble – in Gaza since October 7, 2023, the day Hamas launched an attack on villages and army outposts in southern Israel and Israel began its bombardment. More than 470 Palestinians have been killed since a ceasefire was announced by Trump on October 10 last year.

Presented as a plan to rebuild the Palestinian territory, the Trump administration’s proposal this week, however, offers no insight into core issues such as property and land rights — let alone justice for war crimes — amid plans to construct shimmering buildings atop an estimated 68 million tonnes of rubble and war debris, where thousands of bodies remain buried.

Praising the redevelopment plan, Trump, who also spoke at length at the forum in Davos, argued that the war in Gaza “was really coming to an end”, even as Israeli forces killed at least 11 Palestinians, including two children and three journalists, in separate strikes on the Gaza Strip on Thursday.

“I’m a real estate person at heart, and it’s all about location,” Trump said about the development plan. “And I said, look at this location on the sea, look at this beautiful piece of property, what it could be for so many people.”

Experts have strongly criticised the “imperialist” vision of Trump’s so-called master plan, which they say does not include any consultation with Palestinians and reduces the ongoing catastrophic genocide to an “investment opportunity”.

Trump’s proposal reeks of “imperial plans for Gaza,” Palestinian-American writer Susan Abulhawa wrote in a post on X. “This is a plan to erase Gaza’s indigenous character, turn what remains of her people into a cheap labor force to manage their ‘industrial zones’ and create an exclusive coastline for ‘tourism’.”

During more than two years of bombardment on Gaza from October 2023, Israel, which is diplomatically supported and armed by the US, destroyed or damaged more than 80 percent of the Strip’s buildings, with residential blocks completely flattened.

All major hospitals and universities, and most of the Strip’s electricity and water systems, roads and municipal services have been destroyed.

Nearly all the territory’s 2.3 million residents have been displaced, many of them multiple times. People face hours-long queues for basic food and water, and aid into the territory has been restricted by Israel, which controls everything that goes in and out.

So, what’s in the Gaza reconstruction plan, part of Trump’s launch of a “Board of Peace”; could it be realised — and at what cost, especially for the people of Gaza?

What’s the Board of Peace?

In Davos on Thursday, Trump formally announced the charter for his “Board of Peace”, which he has pitched as the next phase of his administration’s 20-point peace plan and a mechanism to oversee the reconstruction of Gaza. Membership on the board has a three-year cycle. Those seeking a permanent seat must pay $1bn.

But the 11-page charter for the Board of Peace does not mention Gaza and appears to have morphed into something far more ambitious – an international disputes forum and a potential rival to the United Nations.

The executive board so far includes former United Kingdom Prime Minister Tony Blair, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Kushner, with Trump as the chairman himself with veto power. It also includes Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, even though he faces an arrest warrant from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for war crimes in Gaza.

At least 50 countries’ leaders have confirmed that they have received invitations, including US adversaries China and Russia — and several have agreed to join. However, Trump withdrew Canada’s invitation on Thursday, in what appeared to be a retaliatory move following Prime Minister Mark Carney’s speech at the World Economic Forum, in which he denounced Trump’s aggressive stance over Greenland.

Speaking at the forum, Trump said the board was going to be “very successful in Gaza” and “we can spread out to other things as we succeed with Gaza”.

Kushner then outlined details about the board’s development plans for Gaza without mentioning plans for a path to Palestinian statehood.

Hamas, which currently governs Gaza, condemned the proposal, saying: “Our people in the Gaza Strip will not allow these plans to pass.”

What’s in the Gaza plan?

Trump’s development plan includes projections to raise Gaza’s gross domestic product (GDP) to $10bn by 2035, after the size of the territory’s economy crashed to just $362m by 2024 amid the war; 500,000 new jobs; and at least $25bn in investment for modern utilities and public services.

Kushner did not specify who would fund the redevelopment. “As you guys know, peace is a different deal than a business deal, because you’re changing a mindset,” he said, calling the Gaza peace efforts “very entrepreneurial”.

However, he also focused on security. “[The] number one thing is going to be security,” Kushner said. “Without security, nobody’s going to make investments, nobody’s gonna come build there. We need investments in order to start giving jobs,” Kusher said.

He added that the US is working “very closely with the Israelis to figure out a way to de-escalation, and the next phase is working with Hamas on demilitarisation”.

There is no evidence that Palestinians or their leadership have been consulted over any of these plans. Amjad Shawa, director of the Palestinian NGOs Network in Gaza, said Palestinian civil society and official bodies were not included in discussions with the Board of Peace.

“We were surprised, as Palestinian actors on the ground, after 10 years of work, and especially the last two years of work in Gaza, that no one consulted us about the plans for Gaza and its future,” he said.

“At the time these leaders are holding ceremonies, Israel is using this period to continue its actions in Gaza.”

Here are some of the highlights of Trump’s redevelopment plan:

Four phases of development

Presenting a four-phase development timeline beginning in Rafah, southern Gaza, and then moving its way north, Kushner displayed colour-coded maps showing coastal tourism zones, mixed-use towers, and residential and industrial areas, as he unveiled the plan in Davos.

Phase one of Trump’s plan for rebuilding is set to start in Rafah, Gaza’s southern-most city, and some parts of Khan Younis. Phase two will include other parts of Khan Younis, while phase three aims to develop refugee camps in central Gaza. Phase four will cover Gaza City, which is in the north of the territory.

Kushner told attendees at Davos that construction of new developments in all these areas will take two to three years. However, he did not provide details about where Palestinians would live during reconstruction, and how new properties would be allocated.

Coastal tourism plans

In maps showing the Gaza plan, Trump’s administration has pink-coloured nearly the entire seafront and marked it as a “coastal tourism” zone that will include as many as 180 skyscrapers.

The proposal also shows a port at the southwestern end of Gaza, alongside the border with Egypt, and an area zoned for an airport close by, a few miles from the site of the original Gaza airport, which was destroyed in Israeli attacks two decades ago.

Employment and investment

In a report published in October 2025, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics said unemployment in Gaza rose by 80 percent during the war, with more than 550,000 people currently without jobs.

GDP plunged 83 percent in 2024 compared with the previous year, and by 87 percent over two years to $362m. GDP per capita plummeted to $161 annually, placing it among the lowest in the world.

“Before the war, the Gaza Strip witnessed economic growth, with the opening of many commercial, tourism, and industrial projects, and it became a haven for many investments in all sectors,” Maher Altabbaa, the director-general of the Gaza Governorate Chamber of Commerce and Industry, told Al Jazeera earlier last month.

The proposal presented by Kushner claims more than 500,000 jobs in construction, agriculture, manufacturing and services will be created, with a $1.5bn investment in an initiative called “Vocational Schools and (Re)-Training for Full Labor Force”.

He added that the board aims to use “free market principles” to shift Gaza’s dependence on foreign aid, and unveiled plans for a new “logistics corridor”, a new “trilateral” crossing at Rafah, and roads connecting Gaza’s urban centres in the proposal. The plan seems to suggest the new crossing would be built at the point where Gaza, Israel and Egypt’s Sinai region meet.

The main, existing Rafah crossing between Gaza and Egypt, meanwhile, is expected to open in both directions next week.

‘New Rafah’, ‘New Gaza’

Kushner presented a slide showing artificial intelligence-generated images titled “New Rafah”, which showed plans to build more than 100,000 permanent housing units in Gaza’s southern city.

About 200 schools and more than 75 medical facilities will be built, he claimed.

Another slide, titled “New Gaza”, showed plans to turn the enclave into a centre of industry, heavy on data centres and other digital infrastructure.

What did Kusher say about demilitarisation?

Kushner said the reconstruction plan would only commence following full disarmament by Hamas and the withdrawal of the Israeli military after that.

Israel backed several armed groups and gangs in Gaza during the war, and Kushner said these would either be dismantled or “integrated into” the National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG) — a body of 15 Palestinian technocrats tasked with the day-to-day running of the territory.

All of Hamas’s heavy weapons are to be decommissioned immediately, and the remaining smaller arms would be decommissioned gradually by a new Palestinian police force, under the plan. Hamas, on its part, has not committed to disarming – amid worries that this could eliminate what little armed resistance Palestinians in Gaza might be able to offer to future Israeli attacks.

During the presentation in Davos, Kushner’s slide presentation said that Hamas members who cooperate and disarm would be “rewarded with amnesty and reintegration, or safe passage”, and some would be “integrated” into the new Palestinian police force after “rigorous vetting”.

Mahmoud Abbas, president of the Palestinian Authority (PA), has called for the full implementation of the peace plan, including the withdrawal of Israeli forces and a central role for the PA in administering Gaza.

Syrian government takes over prison with ISIL-linked detainees in Raqqa

The Syrian government says it has taken over control of al-Aqtan prison, a facility in the northeastern city of Raqqa housing a number of ISIL (ISIS) detainees, following the withdrawal of Kurdish-led SDF fighters under a ceasefire agreement.

The Interior Ministry said in a statement on Telegram on Friday that officials from the Prisons and Correctional Facilities Administration had assumed control of the prison in the former SDF stronghold of Raqqa, and had begun an examination of prisoners’ conditions and their records, the state-run SANA news agency reported.

The takeover of the prison and cessation of hostilities in Raqqa occurred in line with a four-day ceasefire agreement between the Syrian government and the SDF, which came into effect on Tuesday night. The ceasefire followed last week’s lightning advance by Syrian forces in which they retook large swaths of territory long held by the SDF.

Convoys of buses and cars carrying more than 1,000 SDF personnel were seen moving out of Raqqa, as Syrian forces granted them safe passage to travel westwards to Kobane, a Kurdish-majority city on the border with Turkiye.

The Syrian army’s operations authority said units had also begun transferring SDF elements from the al-Aqtan prison and its surroundings in Raqqa governorate to the city of Ain al-Arab, east of Aleppo, in line with the ceasefire agreement, SANA reported.

Security vacuum filled

Reporting from Raqqa, Al Jazeera’s Zein Basravi said Syrian forces had filled the power vacuum left by the retreating SDF forces “very quickly”, and teams had begun demining and dismantling munitions left inside the prison, removing SDF weaponry on large trucks.

“The Syrian army is now squarely in control of the prison,” he said, describing the “relative smoothness” of the handover as a “positive development”.

He described the developments in Raqqa as a “rare occasion where the SDF and the Syrian military … have acknowledged that they have cooperated and they have done so successfully”.

“It’s the first time that I can remember covering this story for the last couple of weeks that they’ve both acknowledged that they’ve worked together to secure safe passage for SDF fighters,” he said.

Calm restored following chaotic standoff

The situation at the prison, which has been the site of clashes in recent days, was now “calm”, he said, noting “it wasn’t like this here 24 hours ago.”

An Al Jazeera team reporting from outside the prison on Thursday witnessed chaotic scenes as large crowds of civilians pushed against the barricades controlled by Syrian soldiers, with SDF fighters remaining inside.

One soldier told Al Jazeera the Syrian government forces were waiting to see if they would need to retake the prison by force.

Basravi said the civilians were trying to get through the barricades into the prison to find out the condition of their relatives who were detained inside, some of whom they had not heard from in days amid the instability.

Some claimed their relatives had been detained unjustly by the SDF.

“My son was going to visit his relatives in Hasakah,” said one man, Mohammad Ali. “The SDF detained him at a checkpoint just because he had a photo of Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa.”

Amid the chaotic scenes outside the prison on Wednesday, gunfire was heard in the distance, Al Jazeera teams on the ground reported.

Meanwhile, US planes dispatched by CENTCOM were heard overhead as they began flying ISIL detainees out of northeast Syria to Iraq, as part of a push to secure thousands of suspected fighters amid concerns over instability in Kurdish-run prisons.

Securely behind bars

Basravi said that with its takeover of the prison, the Syrian government now found itself answerable to two groups with demands over the detainees, requiring it to strike a delicate balance.

It had obligations to the international community – specifically the anti-ISIL coalition, which it joined in November last year – to ensure that ISIL detainees remained securely behind bars.

But it also faced pleas from locals who claimed their loved ones had been unjustly detained by SDF forces who previously controlled the prison.

He said a visit by senior officials to the prison on Friday, and the Interior Ministry’s statement that it was examining the files held on those inside, was a “positive development” in assuaging the concerns of the latter group.

But while families remained in the dark over the condition of their detained relatives, a repeat of Thursday’s scenes were possible.

Wider implications

Speaking to Al Jazeera from Beirut, analyst Armenak Tokmajyan said he believed the SDF was being genuine in its negotiations with the Syrian government, as they were now “cornered in a few pockets in northeast Syria”.

“However, there is still a risk of the ceasefire collapsing and going back to fighting, said Tokmajyan, a nonresident scholar at the Malcolm H Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center. “There are a lot of details that need to be ironed out, specifically relating to Kurdish-majority areas – whether [around] governance, weapons, integration of Kurdish fighters.”

He said developments in the northeast were being closely watched, particularly by the Druze in the south and Syria’s other minorities, as they held broad implications for whether Syria would be a unified, centralised state or one granting autonomy to minority groups.

The Syrian army’s rapid advance in the northeast had been “a major step forward for President al-Sharaa and those international backers who want a centralised and a unified Syria”, he said, adding that the battle was “not really over”.

“It will depend on how the integration of the Kurdish minority in Syria will look like,” he said. “Everyone is watching if Ahmed al-Sharaa will successfully and peacefully be able to offer a model for reintegrating the SDF into Syria.”

Anxiety, anger, and hope in Syria’s Damascus after SDF ceasefire

Damascus, Syria – Damascus had breathed a sigh of relief when a ceasefire between the Syrian government and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) was announced on the night of January 18. Fireworks lit up the sky, car horns blared and Syrians gathered in Umayyad Square to dance in jubilation.

The hope was that the conflict that flared up in the past few weeks in northern Syria was now over, and that the country had resolved one of the major issues still dividing it in the year since the overthrow of longtime leader President Bashar al-Assad.

“It’s a beautiful feeling, and I am sure it exists in every Syrian … we wish for all of Syria to be united,” said one Damascus resident, Saria Shammiri.

Yet the celebration was short-lived.

Fighting resumed the next morning as the government’s lightning push forced SDF leader Mazloum Abdi to accept less favourable terms: a withdrawal from Raqqa and Deir Az Zor, in northeastern Syria, further east towards Hasakah, a new ceasefire, and a four-day ultimatum for the SDF to fully integrate into state structures.

Anger towards the SDF

As the clock ticks down on that deadline, in Damascus and other areas outside SDF control, frustration towards the Kurdish-led forces has hardened after 15 years of division.

“The terrorist SDF doesn’t belong to this land … they are not Kurdish. They are occupiers,” said Maamoun Ramadan, a 75-year-old Syrian Kurd living in Damascus.

For many here, the SDF is no longer seen primarily as a force that fought ISIL (ISIS) at the height of Syria’s war, but as an actor that entrenched a parallel authority backed by foreign powers, such as the United States, keeping large parts of the country beyond the central government’s reach.

In cafes, taxis and government offices, the language is increasingly blunt. The SDF is accused of delaying reunification, monopolising oil and agricultural resources in the northeast, and shielding itself behind US support while the rest of the country endured sanctions, collapse and war. The renewed fighting has reinforced a belief among many Syrians that the standoff could only ever end through force or submission. But, still, many want a peaceful resolution.

“Dialogue is the foundation of peace,” said Sheikhmos Ramzi, a butcher, “the solution lies at the negotiation table. Violence only brings more violence.”

Anxious wait

There is also an undercurrent of anxiety. While the prospect of reunifying territory is popular, few in Damascus are blind to the risks. A prolonged confrontation could draw in regional actors, unsettle fragile border areas, or reignite communal tensions in the northeast, where Arab tribal communities, Kurds, and others coexist uneasily after years of shifting alliances.

Some residents privately express concern about what integration will actually mean on the ground. Will SDF fighters be absorbed into national forces, sidelined, or prosecuted? Will local administrations be dismantled overnight? And can a central state, stretched thin after years of war and economic crisis, realistically govern and stabilise territory it has not controlled for more than a decade?

For now, however, those questions are largely drowned out by a dominant mood: impatience. The ceasefire was welcomed not as an endpoint, but as a step towards what many here see as an overdue resolution. The government’s advances are framed as restoring sovereignty, not opening a new chapter of conflict.

In Damascus, unity is the word repeated most often. But it is a unity shaped by exhaustion, resentment and the desire to finally close one of the last unresolved fronts of Syria’s long war.

Is the UK playing a double game in Sudan and Somalia?

In December, as it often has during the ongoing war between the Sudanese army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the British government urged accountability, expressing concerns about the mass-scale death and devastation that civilians have suffered.

But reporting has shown that, behind the scenes, the United Kingdom rejected more ambitious plans to prevent atrocities as violence escalated.

Further east, the UK has officially backed the territorial integrity of Somalia – while holding a stake in a strategic port in the breakaway region of Somaliland that it does not recognise.

These decisions and moves by the UK, say analysts, raise doubts about whether its words are in keeping with its actions in the Horn of Africa.

Amgad Fareid Eltayeb, a Sudanese policy analyst, said the UK’s credibility is increasingly judged by the risks it is willing, or unwilling, to take.

“When people believe your words and your actions diverge, they stop treating you as a broker and start treating you as an interest manager,” he told Al Jazeera.

‘Enabler of aggression’ in Sudan

That judgement, analysts argue, now colours how the UK’s actions elsewhere in the region are being read.

In Sudan, earlier reports show how the UK government opted for what internal documents describe as the “least ambitious” approach to end the bloodshed, even as mass killings by the RSF mounted in Darfur, including around el-Fasher.

Eltayeb argues that this has led the UK to be viewed not as a marginal or distracted actor, but as a central one whose diplomatic posture has helped shape how the war is framed internationally.

He referred to reports that the United Arab Emirates has armed or supported RSF – allegations documented by UN experts and international media and denied by Abu Dhabi – and said the UK had emerged as “an enabler of the Emirati aggression in Sudan”. The aim: To “whitewash RSF atrocities in the diplomatic framing of the war”.

Asked about its approach to Sudan, the UK Foreign Office told Al Jazeera: “The crisis in Sudan is the worst we have seen in decades – the UK government is working with allies and partners to end the violence and prevent further atrocities from occurring.

“We need both the parties to support a ceasefire; this means unrestricted humanitarian access and a peace process with transition to a civilian government.”

Recognise Somalia, do business with Somaliland

The Foreign Office did not respond to questions about the UK’s role in Somalia or its commercial engagement in Somaliland, where scrutiny has increasingly centred on the port of Berbera.

The British government co-owns the port through its development finance arm, British International Investment (BII). The port is jointly owned by the UAE-based logistics firm DP World and the government of Somaliland – even though the UK does not officially recognise that government. The UAE, too, formally does not recognise Somaliland.

Berbera sits near one of the world’s most important maritime corridors linking the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. An impact assessment commissioned by the UK Foreign Office described it as “a strategic gateway” to Somaliland and a potential alternative trade corridor for Ethiopia, language that places it firmly within the region’s geopolitical architecture.

The port’s strategic value is not new. Matthew Benson-Strohmayer, a social and economic historian of Africa at the London School of Economics (LSE), noted that Berbera has repeatedly been treated by external powers as strategic infrastructure first, and a political community second. It has served at different points as a British coaling station, a Soviet naval base during the Cold War, and now a commercial logistics hub shaped by Gulf and Western interests.

The Sudan-Somaliland link

That wider architecture has become more politically charged as Sudan’s war has spilled across borders.

Observers have suggested that Berbera is part of a broader Emirati logistics network that United Nations experts and international media have linked to alleged supply routes used to arm the RSF. The UAE has consistently denied these allegations.

For critics, the UK’s commercial entanglement with that alleged network raises uncomfortable questions. While London publicly calls for accountability in Sudan, it remains financially tied, via the BII, to a port operated by the UAE, a close regional partner accused of backing one side in the war next door.

Abdalftah Hamed Ali, an independent Horn of Africa analyst, said this highlights what many critics see as “a gap between principle and practice”.

“Even if London disputes those linkages,” he said, “the perception problem remains.”

The sensitivity has deepened as Somaliland’s political status has returned to the diplomatic spotlight. Last month, Israel became the only country to formally recognise Somaliland’s independence, a move condemned by Mogadishu and rejected by the wider international community.

For analysts, these developments underscore why claims that economic engagement can be kept separate from politics are increasingly difficult to sustain.

Ali said Berbera cannot be treated as a neutral commercial asset.

“Ports in the region are not just economic assets; they are nodes in a security and influence ecosystem,” he said. “When investment touches ports, free zones, and long-term trade access, it becomes politically legible. People interpret it as strengthening one authority’s bargaining position, whether that is the intention or not.”

In Somaliland’s case, that political legibility cuts several ways: Reinforcing its de facto autonomy, reshaping regional alliances, and entangling external actors, the UK included, in a dispute London – officially – says should be resolved through dialogue rather than external alignment.

Ali described the UK’s approach as a “dual-track” policy.

“Britain maintains its formal diplomatic line with the recognised Somali state, but it also works with Somaliland as a de facto authority because it is stable and functions and controls territory,” he said.

LSE’s Benson-Strohmayer explained that after declaring independence in 1991, Somaliland was excluded from international recognition and large-scale foreign aid. Early governments were forced to rely on locally raised revenue, particularly taxation linked to Berbera port, a dependence that gave domestic actors leverage to demand representation and accountability.

In 1992, when a transitional government attempted to seize control of Berbera by force, local clan authorities resisted. The standoff ended in compromise, helping to entrench Somaliland’s power-sharing system.

Benson-Strohmayer, who also serves as Sudan Research Director at LSE, described this dynamic as a “revenue complex”, in which fiscal control and political legitimacy are tightly intertwined.

Large external infrastructure investments, he warned, risk undermining that bargain.

“When states can finance themselves through deals with external investors rather than negotiations with local constituencies, the fiscal contract changes,” Benson-Strohmayer said.

Such projects, he added, reconfigure who controls revenue flows, who benefits from the port economy, and who gains political leverage. In territories with unresolved political status, infrastructure investment can enable what he described as “governance through commercial presence” – allowing external actors to extract strategic value while avoiding explicit political responsibility.

Ambiguity by choice

The UK’s position, Benson-Strohmayer argued, exemplifies this ambiguity.

British formal support for Somalia’s territorial integrity, paired with deepening commercial and security engagement with Somaliland, he said, gives it port access, counterterrorism cooperation and commercial returns, while avoiding the political costs of a clear position.

Over time, this can undermine institutional consolidation on both sides: Allowing Mogadishu to avoid meaningful negotiations over Somaliland’s status, while weakening Somaliland’s domestic accountability mechanisms by bypassing local political bargaining.

The UK’s posture in Somaliland has drawn scrutiny before. In 2023, Declassified UK reported that the British government suppressed the release of a report into the killing of civilians during clashes in Somaliland, a decision critics then said prioritised political relationships over transparency and accountability. British officials said at the time that decisions around the report were taken in line with diplomatic and security considerations.

Read together, analysts say the UK’s decisions in Sudan and Somalia reflect a single approach applied in different contexts: Preserving access and partnerships while avoiding moves – diplomatic pressure, public confrontation or policy shifts – that would narrow its room for manoeuvre.

Ali argued that while this approach may secure short-term influence, it carries longer-term costs, particularly in a region as politically entangled as the Horn of Africa.

“In the Horn, where alliances overlap with regional rivalries and the conflict economy, mixed signals can quickly become a liability,” he said. “You lose the moral authority to press for political compromise if local actors think your incentives lie elsewhere.”