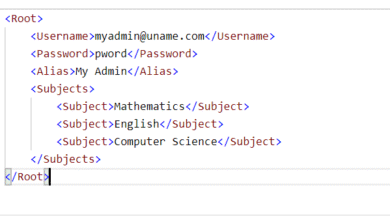

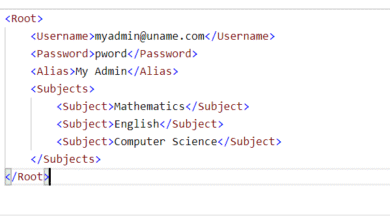

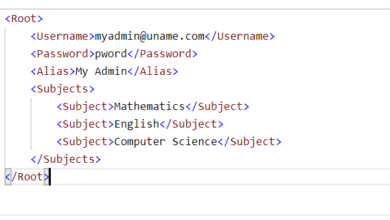

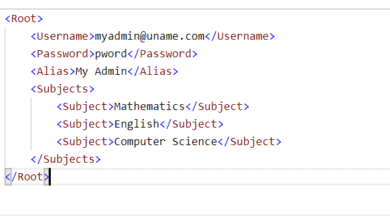

import_all_dw.xml

Lithuania's Defense Minister: 'We will never trust Russia'

What's fueling recent tension between Ukraine and Hungary?

What’s fueling recent tension between Ukraine and Hungary?

August 29, 2025

Ukrainian drone and rocket strikes on the Druzhba pipeline in Russia last Friday disrupted Hungary’s oil supply from Russia.

Right after last week’s attack on the pipeline, Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party went on the offensive rhetorically.

Leading Hungarian politicians called the bombing of Russia’s energy infrastructure “a military attack against the European Union” and “a threat to Europe’s energy security.”

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban even got his “great friend” Donald Trump to chime in, with the American president saying he was “very angry” about the strikes.

Although oil began flowing through the pipeline again on Thursday, relations between Budapest and Kyiv remain tense.

Entry ban for Ukrainian commander

In a further escalation, Hungary on Thursday issued an entry ban against Robert Brovdi, the Ukrainian commander who coordinated and supervised the attack on the Russian pipeline. Brovdi is an ethnic Hungarian Ukrainian citizen.

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy responded to the news by saying it was another attempt “to shift the blame for the ongoing war onto Ukraine.”

Earlier, Hungary’s Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto had claimed on X that “Ukraine knows very well […] that such strikes harm us far more than Russia.” In a separate post, he also wrote that “the latest attack on our energy security is outrageous and unacceptable.”

Is Ukraine targeting Hungary?

Although the Hungarian government has suggested otherwise, experts who spoke to DW say it is implausible that the strikes intended to target Hungary.

“The key here is to undermine Russia’s economic flows, and the main economic flow is through fossil fuel,” Amanda Paul, an analyst with the Brussels-based European Policy Centre (EPC) told DW.

A report by the International Energy Agency found that Russia earned $192 billion (€164 billion) from exporting crude oil and oil product exports in 2024.

According to Paul, Ukraine seeks to weaken Russia’s war economy by cutting off this revenue stream amid Russian advances and wavering US backing.

“Ukraine is not waging war against Hungary. It is defending itself against the Russian aggressor, and if some of the blowback is on Hungary, then so be it,” she said.

Is Hungary’s energy security at risk?

Hungary’s response to the attacks has been so robust because the country is almost entirely dependent on Russian oil imports. Most of this oil comes through the Druzhba pipeline, which has been hit three times within the space of a week.

In a joint letter from Hungary and Slovakia, which also relies heavily on Russian oil, Hungary has even called on the European Commission to take action against Ukraine, claiming it was endangering safe energy supplies.

Similarly, the director of Hungarian oil and gas giant MOL, Zsolt Hernadi, warned of a possible chain reaction: “If oil refineries in [Slovakia and Hungary] have to stop, or run at reduced capacity, that will affect all of Central Europe,” he told Hungarian media.

The EU said on Thursday that it was monitoring the situation, but that it did not consider the bloc’s energy security to be at risk.

EU accession: Hungary’s veto worsens relations

Energy issues are not the only thing straining bilateral relations between Budapest and Kyiv: Hungary’s Fidesz-led coalition is currently the only government blocking Kyiv’s EU-accession talks and has made this a cornerstone of its message..

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has done little to dispel the idea that the pipeline bombings could be related to Hungary’s politics.

“We always supported the friendship between Ukraine and Hungary. And now the existence of the friendship depends on what the position of Hungary is,” the president said during a press conference on August 24, in a play of words on the pipeline’s name: Druzhba means friendship in Russian and Ukrainian.

Hungary’s risky dependence on Russia

Ukraine’s strikes may not be aimed at Hungary, but they certainly expose how vulnerable Viktor Orban has made his country by continuing to rely on Russian oil.

While Hungary and Slovakia were given sanction exemptions by the EU, they have made no effort to reduce their dependency on Russian oil.

“Hungary increased its Russian crude reliance from 61% pre-invasion to 86% in 2024, and Slovakia remained almost 100% dependent,” according to a report by the Center for the Study of Democracy dated May 2025.

Even economically, this reliance is becoming increasingly difficult to justify, as the price of Russian oil has gone up, Tamas Pletser, a Budapest-based oil and gas equity analyst told DW.

“There is still a cost benefit, but it has significantly decreased,” he said.

Pletser warns that with the EU pushing to phase-out Russian fossil fuels by 2027 — coupled with the fact that Ukraine is increasing its capacity to build and use new types of missile that can strike energy infrastructure — “imports have become very risky, which is why I think there is a need to diversify,” he told DW.

Pletser believes Hungary’s oil industry is capable of such diversification, but says there is at present no political will in Hungary to break away from Russian oil.

Why does Ukraine not just shut down Druzhba?

If Ukraine wanted to stop the flow of Russian oil to Europe at any cost, it could do so by shutting down the Druzhba pipeline running through its territory — at least in theory.

But once the pipeline crosses from Belarus into Ukraine, the oil flowing through it legally belongs to the Hungarian company MOL, Pletser explained.

“So, shutting it down would be a serious escalation, and I don’t think the Ukrainians want to confront Hungary like that,” he said, adding that Ukraine earns roughly $200 million a year in transit fees — a considerable source of income for the war-torn country.

Pletser went on to say that targeting pumping stations and other energy infrastructure on Russian soil avoids such a breach of contract and may be Ukraine’s best shot at halting the invasion.

“If Russia is facing energy shortages, that’s the only thing that can stop their military and force Putin to the negotiating table,” he said.

Edited by: Aingeal Flanagan

Russia launches massive attack on Kyiv, hitting EU offices

August 28, 2025

Russian missile and drone strikes hit Kyiv before dawn, damaging nearly 100 buildings and killing civilians. Among the targets was the EU delegation’s HQ. There was strong condemnation from Brussels. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen vowed tighter sanctions. The Kremlin claimed its strikes had targeted military infrastructure, and reiterated an interest in peace talks.

Germany's Pistorius: New Rheinmetall arms plant sends signal

Germany’s Pistorius: New Rheinmetall arms plant sends signal

August 28, 2025

Like many other NATO and EU members, Germany is ramping up arms production to help Ukraine fight Russia’s full-scale invasion in the short term and develop the capabilities necessary to counter any future threats to its security.

In pursuit of those aims, Düsseldorf-based defense contractor Rheinmetall on Wednesday opened an arms and explosives manufacturing plant in the German state of Lower Saxony, the largest munitions factory in Europe.

The factory’s significance was underscored by the fact that NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte was on hand to mark the event alongside Rheinmetall CEO Armin Papperger and German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius.

DW’s Roman Goncharenko spoke with Pistorius about this and other defense manufacturing projects, as well as troop numbers and the possibility of a return to military conscription.

How is Germany ramping up arms production?

Pistorius told DW that the new factory was key to helping Ukraine and that its quick completion sent a message. “That’s what matters: sending the signal that we can do it faster, we want to do it faster, and production is ramping up. These are the crucial signals, for example, and above all for the resilience of the Ukrainian armed forces,” he explained.

Pistorius said the plant would produce 350,000 rounds of ammunition annually from 2027. In underlining Germany’s commitment to “supply Ukraine and help replenish the stocks of NATO partners,” Pistorius noted, “Rheinmetall also plans to build plants in eastern Europe and southeastern Europe, both for explosives and ammunition.”

Speaking of the 14-month completion of the factory, Pistorius told DW that it showed “excellent cooperation between all those involved, whether it be the federal government or the state of Lower Saxony.” Pistorius also praised Rheinmetall and Papperger’s determination, as well as thanking current and previous state and local leaders.

What about German-Ukrainian cooperation and Taurus deliveries?

DW asked Pistorius for his assessment of cooperation between Germany and Ukraine. He said that common ground had been found and that he was impressed by the flexibility and adaptability displayed over and over again by Ukraine’s forces.

“I am very satisfied with the results to date,” said the minister, “but there is still a way to go.”

When asked whether long-range Taurus missiles could be included in security guarantees for Ukraine if a ceasefire is achieved, Pistorius declined to comment, saying only that he would “put them on the table.”

Taurus missiles have been on Kyiv’s wishlist for a long time but Berlin has resisted calls to send them for fear of getting dragged into direct conflict for supplying such lethal long-range capability, preferring instead to invest in new joint production projects as well as supplying US-made Patriot air defense systems.

Will Germany return to military conscription?

DW also raised the issue of whether Germany will reinstate military conscription, suspended in 2011, if the army cannot meet its recruitment targets.

“If there are not enough volunteers and we cannot reach the numbers we want to achieve,” he said, “then compulsory elements will have to be introduced by cabinet and parliamentary decision.”

However, Pistorius voiced optimism, saying the army had “a clear growth path” and that recruiting trends were pointing in the right direction. He said, “We will probably exceed this year’s target of 15,000 recruits,” adding that targets will increase annually after that.

The minister said that Germany plans to train a total of just under 110,000 new reservists between now and the end of 2029. He added that this is exactly the target the country is aiming for.

Edited by: Dmytro Hubenko

'I didn't want to leave': Fleeing Russia's advance in Donbas

‘I didn’t want to leave’: Fleeing Russia’s advance in Donbas

August 28, 2025

“We’re sitting on our suitcases,” a woman named Natalia said in Sviatohorivka, a village on the outskirts of the town of Dobropillia, in eastern Ukraine. Russia’s army has advanced to within almost 10 kilometers (6 miles) of her home. Ukrainian soldiers have managed to retake some places from Russia, but the villages all around are still under constant bombardment.

The only reason Natalia hasn’t left Sviatohorivka yet is that her elderly parents refuse to evacuate. “My father says, ‘I was born here, and this is where I’ll die,'” Natalia said. “And I say: ‘You will die. But who will bury you when everyone is gone?'”

DW met with Natalia in an almost-deserted village for an evacuation organized, with the help of volunteers, by officers from a special Ukrainian police unit known as the White Angels.

Evacuating people in Donbas is dangerous, so the group travels in an armored vehicle equipped with electronic combat equipment. David, a volunteer from the AURA charitable mission, is driving, while police officer Ilia Malzev studies the map. They have to pick up people at two different addresses in Sviatohorivka.

‘And where will I live?’

Seventy-four-year-old Maria is waiting at the first address. She’s already packed her belongings. A policeman collects her bags while a volunteer helps her to the car. Maria can only walk slowly, leaning on a cane. Finally she gets into the vehicle, breathing hard.

“The drones fly straight at us. I actually wanted to stay; I thought, well, I’m already old. But this life is forcing me to go. It’s unbearable; there’s only one neighbor left on our street, everyone else has gone,” she tells us.

The aid workers can’t immediately locate the second address. Hardly anyone here knows 70-year-old Tetiana, whose name is on the list of people to be evacuated. Finally, a police officer finds her in one of the abandoned houses. She took refuge here a week ago, after her house in nearby Dobropillia was destroyed by missiles. “I had to leave all my things behind,” she tells us.

“Come on, let’s go! There’s no point staying here,” Malzev tries to persuade Tetiana. The old lady buries her face in her hands. She doesn’t want to go with the helpers at first, but in the end she thanks them. “And I thought everyone had forgotten me,” she says, and smiles.

On the way out of Sviatohorivka, the 70-year-old asks where she will collect her pension in future. “Where you’ll be living,” the helpers tell her. “And where will I live?” she asks.

‘The situation has drastically changed’

Finding accommodation for people from the towns and villages near the frontline is as difficult as the evacuation itself, says Konstantin Tunyzkyi, another White Angels policeman who is himself an internally displaced person. Tunyzkyi is originally from in the city of Kurakhove, which has been occupied by Russia since the start of this year.

The evacuees from Dobropillia, Sviatohorivka, and other villages are initially brought to a staging post in the Donetsk region, where volunteers from various charitable organizations are active. They then take people further west, to the region of Dnipropetrovsk, where they’re either put on trains or put up in emergency shelters. This week, the number of evacuees far exceeded the available accommodation, and many had to sleep in tents.

Tunyzkyi says they’re receiving dozens of evacuation requests every day from people in and around Dobropillia. “A whole apartment block in Dobropillia was destroyed by a guided missile. Five people waiting for us had spent the night there,” he reports. “The situation has drastically changed.”

He explains that if the evacuation units are unable to go into an area because it’s too dangerous, they tell people to leave on foot. On one occasion they received a call from an elderly couple. “There was heavy fighting in the village of Nikanorovka. An elderly couple with walking difficulties brought a bedbound old woman to the neighboring village of Bilezke in a wheelbarrow,” he says. “They said Russian soldiers had shot the woman’s son, as well as her neighbors, who were hiding in the cellar.”

‘People quickly packed up their things’

People are also leaving Dobropillia and the surrounding area in their own vehicles. A car with a white ribbon and a trailer attached stops at the evacuation point. The ribbon is intended to protect it from Russian drones, while the trailer is to transport her entire life somewhere else, explains Natalia, the owner of the car. She, her husband, and their cat have just left Dobropillia.

“A lot of houses there have been destroyed. The town feels really creepy. People quickly packed up their things and left,” she says. “To be honest, I don’t know what we’ll do next. I have to get over all this first.”

Natalia and her husband are headed for Ternopil in western Ukraine, where they plan to visit their son. He was a soldier in the army, but was invalided out after being injured. Natalia’s mother is still in Dobropillia. “I couldn’t persuade her,” Natalia sighs.

“People do sometimes refuse to be evacuated. Usually it’s because relatives have put them on a list, but they didn’t ask for it themselves,” Tunyzkyi explains. The helpers try to convince them. “There’ll come a time when no one will be able to get to them anymore.”

‘My advice is: Get yourself to safety’

Fifty-six-year-old Oleh from Pokrovsk knows what it’s like not to want to leave. “My advice is: Get yourself to safety,” he urges. Oleh has injuries to his face, a suture above his eye, and a bandaged hand. He left Pokrovsk on a bicycle. “I got away. I was lucky. But all along the road there were broken bicycles, broken-down motorbikes and cars.”

Three days earlier, a Russian combat drone flew into Oleh’s garden. “It was like a little plane, going round in circles. I didn’t realize it was so dangerous. The sudden explosion almost burned out my eyes,” he says. His neighbors came to his aid. As a result of the drone attack, Oleh is now partially blind.

He decided to leave, because not even the hospitals in Pokrovsk are functioning now. “We’re under constant bombardment. Houses are burning. The town doesn’t exist anymore,” he says.

In June, Oleh’s brother was killed by an artillery shell. He had to bury him beside a fence. “Lots of people are buried in gardens,” Oleh says.

“If anyone still has doubts, my advice to them is: Go!” he repeats. Last September, at the start of the evacuation of Pokrovsk, he sent his wife and daughter to Odesa, but refused to leave himself. Back then, he didn’t want to abandon his house.

“I was attached to my possessions. But life is more precious,” he says. Now, as he travels to join his wife and child, his possessions fit into just two bags.

This article was originally written in Ukrainian.

Germany considers return to compulsory military service

August 27, 2025